Post

A woman’s virginity can be proven by an intact hymen

Many of us grew up hearing that a woman’s virginity can be “proven” if her hymen is still intact, a belief whispered by aunties, taught in some schools, and reinforced by cultural expectations.

For years, girls have been warned that any physical activity could “break” it, or that if they didn’t bleed on their wedding night, they were no longer pure.

But here’s the truth: this idea has no medical basis. The hymen tells us nothing about whether a woman has had sex or not. It’s one of those deep-rooted myths that science has long disproved, yet it still shapes how women are judged today.

Let’s take a closer look at what the hymen really is and why it can’t be used to measure virginity.

What is the Hymen?

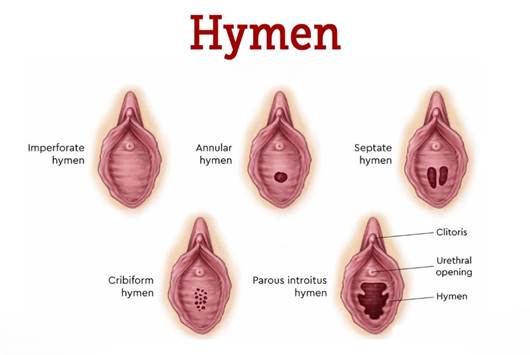

The hymen is one of the most misunderstood parts of the female body. Many people imagine it as a “seal” that breaks during first-time sex, but that’s not how it works at all.

The hymen is simply a thin, elastic fold of tissue that partially covers the vaginal opening. It’s there from birth, and its shape, size, and thickness vary from person to person.

Here are a few things to note:

-

Some girls are born with very little hymenal tissue, while others have more.

-

For some, it may appear as a small ring, crescent shape, or several tiny folds.

-

In a few cases, it might not be visible at all, and that’s completely normal.

-

The hymen can stretch naturally over time, even without any sexual activity.

-

Not every woman bleeds during her first intercourse. Bleeding depends on several factors, not virginity.

-

Some women may bleed the first time due to friction or lack of lubrication, not because the hymen “broke.”

So, the idea of an “intact” hymen is misleading. There’s no single way a healthy hymen should look, and it doesn’t serve as proof of anything, not virginity, not morality, and certainly not a woman’s worth.

Now that we understand what the hymen really is, let’s talk about why it cannot be used to prove virginity.

Why an “Intact” Hymen Doesn’t Prove Virginity

The state of the hymen says nothing about whether a woman has had sex or not. It can stretch, tear, or stay the same for many different reasons, most of which have nothing to do with sexual activity.

The hymen can change due to:

-

Physical activities like running, cycling, dancing, or gymnastics.

-

Use of tampons or menstrual cups.

-

Medical examinations or even accidental injury.

-

Natural growth and hormonal changes during puberty.

In the same way, some women who have had sexual intercourse may still have visible hymenal tissue, while others who haven’t may not. Everybody is different.

That’s why medical experts, including the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Human Rights Office, have made it clear that “virginity testing” or checking a hymen to prove sexual history is scientifically invalid and unethical.

What Virginity Really Means (and Why It’s Personal)

The word virginity often carries so much weight in our culture, especially for women. It’s used to measure morality, and sometimes even worth, but in truth, virginity is not a medical term.

It’s a social and personal idea shaped by beliefs, religion, and tradition, not by biology.

Medically, there’s no test, sign, or physical mark that proves whether someone has had sex. What people call “losing virginity” is simply an event, a personal choice that happens differently for everyone.

Here are a few important points to remember:

-

Virginity is a concept, not a condition. It cannot be seen or medically confirmed.

-

Your worth, respect, or dignity does not depend on your sexual history.

-

Healthy sexuality should focus on consent, respect, and safety, not proof or shame.

Everyone’s journey is different, and that’s okay. What matters most is understanding your body, making informed decisions, and treating others with the same respect.

In Conclusion

It’s time we stop letting outdated beliefs shape how women are seen or treated.

The obsession with “proving” virginity has done more harm than good, leaving behind shame, silence, and mistrust.

What young women need instead is accurate information, empathy, and safe spaces to understand their bodies without fear or judgment.

What are your thoughts? Have you ever heard someone talk about virginity in this way, or faced pressure tied to this myth? I’d love to listen to your perspective.

Researched by Victoria Odueso

Login